“Beresina!” It was painful to see that even those units were at the end of their tether. Behind the unwounded formations came a stream of lightly wounded followed by the server cases. These had been piled into panje carts or onto sleds and, where was no room for them to be carried they had been tied with ropes to be dragged behind the carts, often face downwards, through the snow. The men of Kampfgruppe Peiper gazing the train of misery on carts and sleds from the 320. Infanterie-Division, whispered. “Napoleon’s retreat must have looked like this.”

*************************************

12 February 1943

At 03:30 [Lehmann: 04:30], the KGr Peiper set out from [Lucas: the Kolkhoz of] Podolchow (Podolkov or Podol’okh), into the operation to release the 320th from their encirclement.

In the terms of the operational environment the escape of the 320th was completely different from the breakthrough of the Demyansk encirclement in 1942 or those of Kovel and Vilnius in 1944. A continuous front line was absent both in the external and internal rings of the encirclement. The problem arose out of what was really a relatively long retreat without any communication with the logistic corps. After retreating for almost two weeks, the division had become a shamble that was weighed down by thousands of wounded.

On the other hand, despite the capability of independent operations in almost any terrain, it would be wrong, however, to overestimate the capabilities of KGr Peiper. In essence of his forces were only sufficient to be able to engage in counterattacks on enemy units. He did not have the artillery at his disposal to conduct a full-scale combined-arms battle. The 11th, 12th and 13th (gep.) Kompanie each comprised a Heavy Platoon which consisted of two 81mm mortars and one “Stummel” equipped 7.5cm L/24 guns, and the 14th (sch. gep.) Kompanie consisted of six “Stummel”. [Agte: The first platoon of the 14th Kp of Bn Peiper consisted of four Infantry Guns in towed, while the second platoon held six Sd.Kfz. 251/9 “Stummel”] Even the enemy’s armament, in the shape of the 122mm howitzer, meant that conducting a battle against them would have been impossible without reinforcement or air support, since the disposition of the majority of soldiers in the armored personnel carriers rarely affected their survivability with respect to air attack and artillery fire. This was particularly relevant to the HQ (radio) vehicles. Apart from that the Bn did not have effective AT weaponry, with the absence of panzers in this sub-division, to against Soviet medium and heavy tanks. Realizing this fact, Dietrich augmented Peiper’s force by two assault guns [Agte: Seven assault guns of two platoons, according to the diary of Erhard Guehrs]. In addition, the off-road capability of the KGr however paled into insignificance in terms of the nature of the task that was in front of them: aside from combat material the group consisted of 60 ambulances as well as a considerable number of other lorries not being used.

Peiper’s mission was not a simple one for a group of such modest strength. It was to take the city of Zmiyev (Smijew), ford the Rivers Mzha and Uday in order to pick up the 320th which has been ordered to retreat to Zmiyev via Liman.

By 05:15 the vanguard detachment of KGr Peiper, which was led by two assault guns, had reached the River Uday near the village of Krasnaya Polyana (Красна Поляна). Taken by surprise, the Soviets who had been defending the bridge scattered and the bridge was fell into Germans’ hands intact. [Lucas: Before the start of the operation, Peiper concealed his SPWs in the houses around the wooden bridge across the Uday and at H-Hour led the advance across that bridge and into Krasnaya Polyana.] This was an important success in the first hours of the operation since the half-track armored personnel carriers as well as the assault guns required relatively strong bridges on which to cross even the smallest of streams, and Peiper did not have an engineering sub-division attached to his formation. [Agte: The Forth platoon of the 14th Kp of Bn Peiper equipped four Sd.Kfz. 251/7 with fittings to carry assault bridge ramps on the sides.] Some of the tail end of the lorry column, which had arrived late for the start of the operation, came under fire from Soviet troops in Krasnaya Polyana who had recovered quickly from the surprise of the Germans’ attack and had gone back into action again. Six German lorries were destroyed by the Soviet fire but their drivers were picked up. Peiper, however, was not able to turn around: the Ia told him that a pilot had reported the leading elements of the 320th to be near Liman, it was still too early to be thinking of the home strait.

At 06:40, KGr Peiper captured Zmiyev without encountering any noteworthy enemy resistance and forded the River Severskiy Donets south of the city. A railway bridge across the river fell into his hands. [Lucas: That was an order that Peiper was unable to execute. In the middle weeks of February the ice sheet across the river was thinning and was no longer able to bear the weight of the heavy APCs. Neither was there a bridge across the Donets, nor had his KGr any pioneer detachment that could construct one. He would have to remain on the western bank.] [Lehmann: After the commander of 320th, General G. Postel, appeared with a large vehicle and entourage of offices, Peiper was asked why he had not crossed the River Severskiy Donets. A reference to the weak ice which wouldn’t bear the weight of combat vehicle was swept aside, but at almost the same moment an Ordonnanz-Offizier from the 320th confirmed it by reporting one assault gun had already broken the Ice layer and sunk in.] Having concentrated the principal forces of his KGr in Zmiyev Peiper dispatched several scout teams to make contact with the forward units of 320th.

At 12:30, after nearly six hours the scouts finally established visual contact with their Wehrmacht comrades, the retreating columns of 320th had sprawled out over several kilometres and its rearguard was still in the area around Liman.

At 14:00, the contact was officially established. It was “a train of misery on sleds and carts”. As these were overlooked, some of the unlucky ones were tied to them and pulled along on their stomachs. SS-Ustuf. Erhard Guehrs sent as liaison officer to General Postel remembered, “the division looked terrible, everything defied belief.” In the meantime, Peiper’s surgeons and medics had arranged emergency medical treatments. Demanded by General Postel, KGr Peiper had to provide cover for the 320th assembly area near Tscheremuschnaja (Cheremushne) ─ Sidki (Zid’ky) ─ Samostje ─ Butowka (Butivka).

SS-Hstuf. Paul Guhl, commander of the 11. (gep.) Kompanie, recalled that General Postel’s arrogant appearance, he was still wearing his white detachable collar – in comparison to the ragged, dead-tired Landser of his division, moved him deeply.

*************************************

13 February 1943

Blowing snow. Escorted from both sides by the men of KGr Peiper who had gone on guard and stared into the spooky night, hollow-cheeked, convinced this wasn’t going to last, the column of lorries bearing the wounded and the infantrymen of the 320th set off northward in the early morning.

At 11:50, the columns were confronted with the bridge over the River Uday that had been blown up. The SS platoon that had been guarding the bridge had been completely wiped out. The remains of the bridge were used to construct a temporary bridge. This bridge, however, was too light to support armored vehicles. [Lucas: The village itself was now in the hand of a Red Army ski Bn which had recaptured it from the garrison which Peiper had dropped off. The SPWs of Bn Peiper opened fire cleared Krassnaja Poljana of enemy forces and drove them east after desperate house to house battles.] [Agte: Erhard Guehrs wrote, “There was a hard fighting at Wodjanoje with a Russian ski Bn. By evening we had really cleaned them out. Crossing. My gun had fired 42 shells. We have six dead. By 1900 every element had made it through.“]

Peiper reported numerous German stragglers from the previous day had unfortunately been massacred and mutilated by the Soviets.

At 16:00, all the lorries with their wounded were brought behind German lines. Peiper led his KGr back to Zmieyv. Having reaching the River Mzha, he turned to the west and reached Merefa by moving along the northern bank of the river. [Lehmann: KGr Peiper was forced to take a detour through Butowka, Sidki, Artjuesschewka (Artyukhivka) and Migorod (Myrhorody) in enemy territory.]

*************************************

14 February 1943

At 07:00, the last of elements of the 320th finally crossed the bridge located at Wodjanoje (Vodyane).

At 08:25, General Postel reported to the Armeeabteilung by radio as follows: “Arrival of the last rear guard, Bn 585. With that arrival, the entire 320 missing only those men and equipment lost in battle, was finally massed at the German lines after heavy, uninterrupted fighting to break through. From 26.1 to 14.2, it had been forced to rely completely on itself through a wide expanse of territory while surrounded by enemy forces of at least Bn strength. Now, after meeting its most pressing needs, it stood ready for new deployment.

*************************************

Postscript

[Alexei Isaev:]

In sending the best motorized infantry Bn in his division on a raid, that penetrated the enemy’s lines to quite some depth, Dietrich did of course take a risk. This risk, however, was born out: given a loose front line Peiper’s well equipped, well-protected, and well-armed group had little chance of encountering the enemy [1], which would have been impossible for them to evade, or alternatively to attack and push back. One significant drawback of this action was probably the poor engineering support for the operation. It would have been easier for Peiper to break through in the opposite direction.

It would have been a more piquant situation had one of the bridge been blown up on the way to meet the 320th. It would also been a mistake to attribute the success of this operation to Peiper alone. The actions of his Bn were secured by virtue of defence of the other units to the north of River Uday. It was in the same direction in the area around Lizogubovka (Lyzohubivka) and Ternovoy (Ternova) that the 12th Tank Corps under the 3th Tank Army had been active.

Between only 9-14 February, the 6th Army gained 15 guns, 500 trailers, 35,000 rounds of ammunition, 12,000 shells, 5,000 rifles and 800 automatic weapons, and other armament as trophies. F. M. Kharitonov (the 6th Army) laid claim to 4,000 enemy soldiers and officers, and 1,000 vehicles. The 298th , which the Kampfgruppe [2] were not successful in finding to release them from the encirclement, were completely wiped out.

[Author:]

[1] Compare with the Germans’ initiatives in the rescue of the 320th, Vatutin had been too concentrated on the progress on the southwesterly progress towards River Dnieper. In spite of emphasizing the importance of annihilation of the 320th, the absence of concrete response to the encircled enemy forces eventually led to the successful rescue mission carried out by the KGr Peiper, and Vatutin wasn’t even aware of that the 320th had slipped from his grasp by the morning of 14 February. Weeks later, his long-distance raid ended up fruitless after Germans’ counterattack cut his forces to pieces.

[2] The unit that was accountable for the ill-fated 298th, completely dissolved on April 30 as consequence of the loss inflicted in February, was most likely the KGr Meyer i/o the KGr Peiper. The 298th had most likely been crushed on the Kupjansk-Tschugujew road while KGr Meyer was forced to retreat ahead her under enemy pressure. See Meyer, 2005, Grenadiers, pp. 160-164. Cited below:

(pp. 160-161.) [Approx. in early February] The 298th Infanterie-Division was reforming at Kupjansk [Куп’янськ located in the western bank of River Oskil] after having been severely battered during the withdrawal; (…) The Bn had orders to set up a bridgehead at Tschugujew [Чугуїв] and establish contact with the 298th. (…) The Bn had to cover a front of about 10km and, in addition, two companies had to support the disengagement of the 298th at Kupjansk. (…) The 3./SS-AA 1 succeeded in disengaging from the Soviets on the Kupjansk-Tschugujew road and reached the Bn without serious casualties. The 298th was fighting its way westward through deep snow drifts and icy winds south of the road, having lost all its artillery on trackless open ground. At the moment all contact with the division had been cut off.

(p. 162.) On it (sled) was SS-Uschaf. Krueger who, despite his wounded condition, had succeeded in dragging himself onto the sled and giving the Soviets the slip. I heard from him that there were more stragglers from the 298th in the surrounding area. Within half an hour we had found about 20 members of the division in the huge snowfields on both sides of the road.

(p. 164.) On 8 February… After an advance, contact was successfully made with the remnants of the 298th and the survivors were ferried over the Donez. A gloomy atmosphere reigned over the units at the bridgehead. It was obvious that our position had already been threatened deep on each flank and the units had to be pulled back beyond the Donez.

*************************************

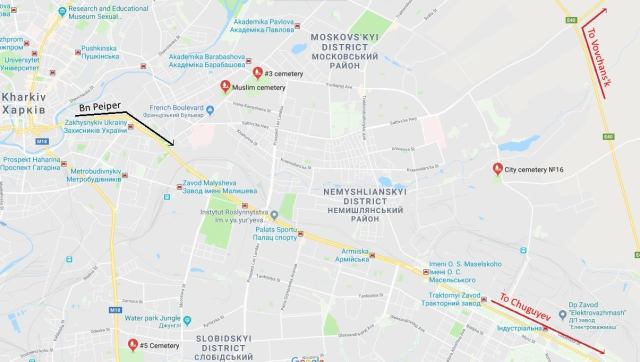

Situation Maps

On 6 February Vatutin issued: (…) Kharitonov’s 6th Army will reach the Taranovka (Taranivka), Efremovka (Yefremivka), and Orel’ka (Oril’ka). (See D. Glantz, Notes to Chapter 4, 96.)

On 8 February, the 6th Guards Cavalry Corps – was selected to break through following a route from Andreyevka (Andriivka)-Bolshaya Gomolsha (Velyka Homil’sha)-Taranovka (Taranivka Таранівка). The cavalry corps was reinforced by the 201st Tank Brigade. (See Isaev, p. 42.)

At 0405 hours on 11 February the Stavka directed Vatutin: (…) Assign the 6th Army the mission to occupy Sinel’nikovo reliably and then Zaporozh’e to prevent the enemy’s forces from withdrawing to the western bank of the Dnepr through Dnepropetrovsk and Zaporozh’e. (See D. Glantz, Notes to Chapter 4, 98.)

In the afternoon of 11 February, the improvised Kampfgruppen from LSSAH and Das Reich failed to recapture Selyonie Borki. (See Isaev, p. 50.)

On 12 February P. S. Rybalko (3rd Tank Army) ordered his formations to capture Kharkov and not allow the troops that had been defending the city to escape. The 6th Guards Cavalry Corps were ordered to form a shield to the west of the city and to take the roads leading away from it to the west and south-west. (See Isaev, p. 49.)

On 12 February, the 15th Tank Corps captured Rogan. (…) While the15th Tank Corps were engaged in the fighting for Rogan, the 12th Tank Corps and the 62nd Rifle Division skirted round the city of Kharkov to the south [such as Merefa]. (See Isaev, p. 49-50.)

On 12 February, KGr Peiper set off to rescue 320th. While the 7th Guards Cavalry Corps (*), and 350th Rifle Division had by that time advanced up to the River Severskiy Donets. (See Isaev, p. 55.)

On 12 February so on, the actions of his [Peiper’s] Bn were secured by virtue of defence of the other units to the north of River Uday. It was in the same direction in the area around Lizogubovka (Lyzohubivka) and Ternovoy (Ternova) that the 12nd Tank Corps under P.S. Rybalko (3rd Tank Army) had been active. (See Isaev p. 59.)

On 12 February 1943, the 7./SS-PzGr.Rgt.2 fought near the western part of Temnowka (Temnivka). The 1. and 2./SS-Pz.Gr.Rgt.2 fought in Borowje. (…) At 14:10, the enemy took possession of the hills south of Krassnaja Poljana and deployed about a regiment to launch continual attacks on the sector Wodjanoje-Kirssanowka (Kyrsanove)-Lisogubowka. (See Lehmann, p. 65.).

On 13.2.1943, the I./SS-Pz.Gr.Rgt.2 fought in Borowoje. At 14:00, the enemy broke through into Lisogubowka, and been repulsed later. Across from the SS-Pz.Gr.Rgt.2, the enemy attacks subsided in the later afternoon, and by nightfall they slacked off entirely. (See Lehmann, p. 68.)

At 0200 hours on 14 February, Vatutin reported: (…) During the day the remnants of the 320th Infantry Division (400–500 soldiers) encircled in Liman tried several times to penetrate toward Zmiev. All of the enemy’s attempts to escape from encirclement were repulsed. The fighting will go on until the enemy is completely destroyed (…) The 6th Army, while holding on to its previous positions, was preparing to resume its offensive on 13 February 1943 and was continuing to destroy the remnants of the smashed 320th Infantry Division in the Liman region with part of its forces. (See D. Glantz, Notes to Chapter 4, 99.)

On 14.2.1943, at 16:50, the KGr Linden repulsed an enemy attack on Lisogubowka. At 20:00, there was a Soviet Attack on Sidki train station and on the southern edge of Borowoje, held by the I./2. It collapsed under concentrated fire from all heavy weapons. (See Lehmann, pp. 71-72.)

(*) The 8th Cavalry Corps was marching toward Voroshilovgrad (Luhans’k) and Debal’tsevo (Дебальцеве) during the early February, and awarded by Stavka with honorific “guards” status in 14 February. See Glantz, Notes to Chapter 4, 100.

*************************************

Citations

Alexei Isaev, 2018, The End of the Gallop, pp. 52-60.

David Glantz, 2011, After Stalingrad, Kindle, 2410-2473.

James Lucas, 2014, Battle Group, pp. 126-130.

Werner Kindler, 2014, Obedient Unto Death, pp. 35-36.

Kurt Meyer, 2005, Grenadiers, pp. 160-164.

Patrick Agte, 1999, Jochen Peiper, pp. 52, 54, 100-102.

Rudolf Lehmann, 1990, The Leibstandarte III, pp. 60-64.

*************************************

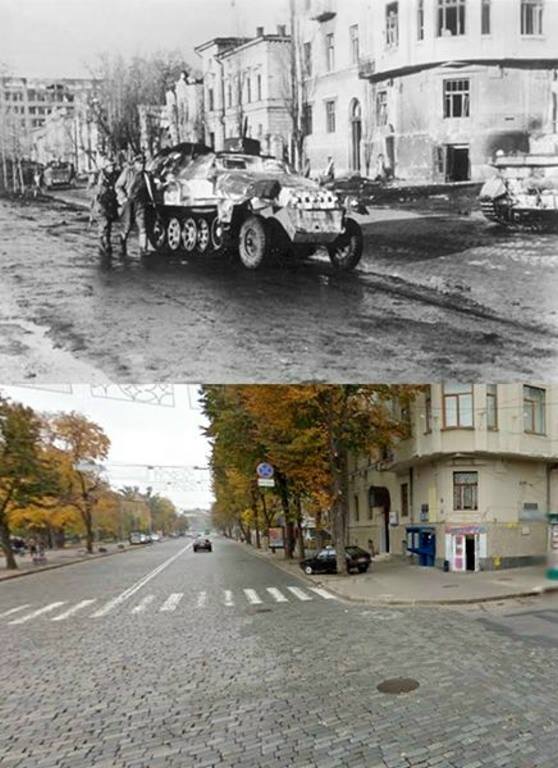

Illustrations of actions

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

49.866667

36.366667