Special thanks goes to comrade Петро Одинець (Peter) for his aide on interpretation.

*************************************

On 8 January 1944. The time just passed at 0000 hours. The Ia of the LSSAH, SS-Ostbf. Lehmann, was at the battalion CP of the III./SS-PzGr Rgt 2, deployed at Point 276.7 taken by the LSSAH’s Panther battalion and handed over to the grenadiers on the morning of 7 January. [1] He was there trying to figure out what the Ivans were up to since their artillery bombardment against Sherebki (a.k.a Zherebky Жеребки) and Stepok (Stepok Степок) had been ceasing for a half hour. [2] It was clear that the enemy, proven to be the 7th Guards Tank Corps and the 350th Rifle Division [3] who had conducted both aerial and ground reconnaissance during the whole day of 7 January, was preparing on the north in order to launch his new attack on the next day.

But when exactly?

SS-Ostuf. Tomhardt reported that there had been loud tank sounds on the southwestern edge of Januschpol (a.k.a. Ivanopol Іванопіль) in the first hours of the night, and the SS-Pz Rgt 1, led by SS-Stbf. Peiper, in Ssmela (Сміла) was put on alert and given orders to move forward as far as the southern edge of Stepok.

At last, at 0500 (while another said 0800 [4]) hours, thirty to forty enemy tanks with infantrymen mounted on them successfully broke through LSSAH’s main battle line at the sector boundary between the SS-PzGr Rgt 1 and 2. The Soviets reached the depression north of Stepok in the SS-PzGr Rgt 1 sector and Sherepki in the III./SS-PzGr Rgt 2 sector. [5]

The situation had turned sour as SS-Obf. Wisch found out that he had already no reserve to cope with such relentless breakthrough. Thanks to the SS-Pz Art Rgt 1, once again, responded swiftly with their concentrated fire, along with fighters of the Luftwaffe arrived the area in the meantime, to blockade the routes, forcing the enemy columns to a standstill, then prevented another breakthrough by aiming their artillery pieces directly on the enemy’s tanks. [6]

Probably owing to the concentrated bombardment, the command of the 54th Guards Tank Brigade, Lt. Col. Vyazemsky, reported the infantry who supposed to coordinate with the tanks closely was somewhat lagged behind. [7] At 0900 hours, he further reported that his brigade had encountered violently counter attacks from three directions. One from Pol’ova Slobidka (Польова Слобідка) with 17 tanks, another from Hutorisko (Хуториско) with 20 tanks and infantry, the other from Krasnopol Pevna (Певна) with 25 tanks and up to two infantry battalions. [8] However, the SS-Pz Rgt 1 reported only 2 Tigers, 11 Panthers and 6 Panzer IV’s fit for combat on 7 January. [9]

But at least he was corret on one thing – the Germans’ counterattack was coming right up. Led by SS-Ustuf. Michael Wittmann, eagerly seeking for fight along with his best partner, gunner Balthasar Woll, who had already had an AT round loaded in the 8.8 cm gun’s breech. He observed the terrain in front of him through the narrow slit in the commander’s cupola. Then he heard the sound of fighting. Machine gun fire and the report of tanks guns indicated proximity to the Soviets.

Suddenly Wittmann saw the enemy tanks and gave Woll through the intercom the position of the T-34 that he intended to hit first. The turret traversing gear quickly brought the gun in the desired direction. Woll tracked the T-34 through his optical sights, and hit it in the turret with his shot. The turret was torn from the tank in a bright jet of flame. “Direct hit!” Then Wittmann had plenty of targets. Woll had already aimed at the next tanks. His crosshairs were placed right at the base of the turret and he destroyed this tank with a direct hit as well – just before it could fire off a round. [10]

On the approach to Stepok, Lt. Col. Vyazemsky continued, the 54th Guards Tank Brigade and 23rd Guards Motor Rifle Brigade were counterattacked by 8 Panzer IV’s and an infantry battalion from Sherebki, with another 17 tanks, 8 of them were Tigers, while the 13./SS-Pz Rgt 1 reported only 4 Tigers fit for combat on 8 January [11], and up to an infantry company from Stepok, and the other 7 tanks from other direction. [12]

By 0900 hours, the LSSAH claimed the dangerous situation had been eliminated. 33 T-34’s and 7 self-propelled guns had been reported destroyed, SS-Ustuf. Wittmann was responsible for 3 of those T-34’s and 1 self-propelled gun, and the Panthers force deployed in and to the east of Sherebki took care of 8 of those T-34’s and 2 self-propelled guns. [13][14][15]

The 56th, 55th and 54th Guards Tank Bridge, along with the 23rd Guards Motor Rifle Brigade, retreated to their departure position around Januschpol.

The 56th reported losing 3 T-34’s, while another 1 T-34 stuck in the swamp, and brigade commander seriously injured, but destroyed 3 Panzer IV’s and 4 guns on 8 January. [16][17] The 55th, claimed been counterattacked by three Panzerjaeger Ferdinand and two Tigers, reported losing 5 T-34’s and suffered 30 casualties, but destroyed 3 tanks, 6 vehicles and 6 carts while inflicted 7 casualties on the enemy. [18][19] The 54th, on the other hand, reported losing 9 T-34’s, 2 SU-152’s on this day. [20] The losses of the 23rd Guards Motor Rifle Brigade was unknown.

At 1200 hours, the 7th Guards Tank Corps reported a combat composition of 29 tanks and 21 self-propelled guns. [21]

In view of the large losses, the 55th and 56th had transferred their remaining tanks to the 54th during the night of 9/10 January. Later on 10 January, the 54th reported a combat composition of 14 T-34’s. [22] On 11 January, it had only 8 T-34’s left when it was asked to transfer its remaining materials to the 91st Guards Tank Brigade, and together with the parts of the 7th Guards Tank Corps it had been withdrawn to the area of Kazatin – without formation. [23]

In July 1942, a standard Soviet Tank Brigade consisted 53 tanks (21 T-60 or T-70’s / 32 T-34’s). By October 1943, the new Tank Brigade consisted 65 tanks (21 T-60 or T-70’s / 44 T-34’s).

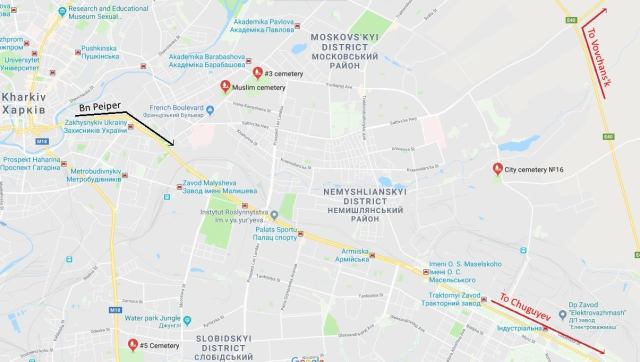

Interestingly, Lt. Col. Vyazemsky also claimed the 54th had been hit by a pincer attack by the 7. Panzer Division and the LSSAH on 8 January. [24] However, the 7. Pz Div was actually operating in the area of Lyubar (Любар), about 35 km WNW of Zherebky, [25] and the only reinforcement from the outside mentioned by the others was the Pz Zerst Btl 473 formed by foot soldiers equipped Ofenrohre with a few horses for carrying the ammo. [26]

During the evening, Balck called PzAOK 4 headquarters and spoke to Raus. [27] He believed his Korps had achieved a major success during this day, particularly with the LSSAH destroying all those Soviet tanks that had broken through to the Zherebki area. [28]

When the darkness fell on the vast ground of Ukraine again, Peiper’s orderly officer, SS-Ustuf. Koechlin, climbed on his Panther, he was attached to the 7. Panzer-Division along with twelve tanks of the SS-Pz Rgt 1. The Point 276.7, in the meantime, was eventually abandoned.

*************************************

[1] Patrick Agte (1999). Jochen Peiper, p. 271.

[2] TsAMO, Fund 315, Inventory 4440, Case 20, p. 23.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Patrick Agte (1999), p. 271.

[6] Thomas Fischer (2003). The SS-Panzer-Artillery Regiment 1, p. 155.

[7] TsAMO, Fund 315, Inventory 4440, Case 20, p. 23.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Rudolf Lehmann (1990). The Leibstandarte III, p. 394.

[10] Agte (1999), p. 271.

[11] Wolfgang Schneider (2005). Tigers in Combat II, Kindle 1458-1460.

[12] TsAMO, Fund 315, Inventory 4440, Case 20, p. 23.

[13] Fischer (2003), p. 155.

[14] Lehmann (1990), p. 396.

[15] Recommendation for award of the Knight’s Cross to Wittmann dated 10 Jan 1944. See Agte (1999), p. 271.

[16] TsAMO, Fund 3150, Inventory 0000001, Case 0004, p. 110.

[17] TsAMO, Fund 3406, Inventory 1, Case 81, p. 16.

[18] TsAMO, Fund 3152, Inventory 0000001, Case 0012, p. 12.

[19] TsAMO, Fund 3406, Inventory 1, Case 81, p. 16.

[20] Ibid.

[21] TsAMO, Fund 236, Inventory 2673, Case 1400.

[22] TsAMO, Fund 3406, Inventory 1, Case 81, p. 17

[23] TsAMO, Fund 315, Inventory 4440, Case 20, p. 24.

[24] TsAMO, Fund 315, Inventory 4440, Case 20, p. 23.

[25] Stephen Barratt (2012). Zhitomir-Berdichev Volume 1, p. 279.

[26] Lehmann (1990), p. 396.

[27] PzAOK 4, Ia Kriegstagbuch entry dated 8 Jan 1944.

[28] Barratt (2012), p. 279.